Major Parts of Japanese Swords – A Visual Reference

From: https://www.swordsofnorthshire.com/swords-of-northshire-blog/sword-anatomy:-parts-of-a-katana-blog

A katana was one of two swords that Samurai wore in feudal Japan and was a very important part of their training, lifestyle, and beliefs. Because these weapons had such important significance, their construction and forging required the utmost care. Besides the type of steel and the actual forging method, it is critical for any master smith and student of the sword to understand the parts of a katana and the sword’s anatomy. If you’re curious about this aspect of Japanese culture, read on here for a breakdown.

From: http://www.japaneseswordindex.com/glossary.htm

Major Parts of a Japanese Sword Blade

Japanese sword blades were/are made in a variety of lengths. The blade is classified by its length. A daito (long sword),either a tachi or katana, is over two shaku (one shaku equals approximately 12 inches or 30 centimeters) in length. A shoto or wakizashi has a blade length between one and two shaku. A tanto blade is normally under one shaku in length. The length of a sword blade (nagasa) is measured from the tip of the kissaki in a straight line to the mune-machi.

A traditional katana is crafted to equal about two shaku or 60cm. They have a slight curve and a single sharpened edge. The most important parts of a katana blade include

- Mune: This is the back edge of the blade

- Ji: The softest section of metal in the back of the blade

- Ha: The harder section of the metal at the front of the blade

- Kissaki: This is the slightly rounded tip of the blade

- Shinogi: The ridgeline of the blade (not the same as the hamon line).

The hamon line is a very important part of the blade that naturally forms through the differential tempering process the metal undergoes. This line separates the higher temperature and lower temperature metal tempering. Some sword makers can be identified by the unique hamon line they create in their swords.

Major Parts of a Buke-Zukuri Koshirae

The buke-zukuri style of sword mounting is the most common type seen today on antique Japanese swords. It is also called the uchigatana or katana style. A set of swords consisting of a long sword (daito) and a short sword (shoto) which are mounted in identical koshirae are referred to as a daisho. Daisho or daito could only be worn by samurai or higher rank, whereas the short sword (shoto or wakizashi) could be worn by merchants, tradesmen and craftsmen. This accounts for the increased value of daito (katana or tachi) versus shoto and for the greater numbers of shoto (wakizashi) found today. Swords in buke-zukuri mountings are worn edge up with the saya thrust through the obi (waist band).

Occassionally the saya of katana, wakizashi or tanto (never tachi) will have slots for various types of accessories to be carried. There are several types of utensils which may be found. The most common is a kozukaor small knife. [Technically the kozuka is just the handle, the blade is the kokatana or gokatana] This is a general utility knife, used much like a pocketknife. A kogai is a hair arranger and ear wax cleaner. The wari-kogai or waribashi is like a kogai which is split in the middle and can be used as chopsticks. The umabari is a one piece, all steel implement of triangular cross-section. All of these were made by skilled artisans and are highly sought after by collectors.

The tsuka is the handle of part of the katana and involves several intricately detailed components.

- Mekugi: These are wooden pegs that adhere the tang of the blade to the hilt.

- Samé: This is the material that covers the hilt of the sword. It’s traditionally ray skin.

- Ito: This is a silk wrap that covers the samé for better grip of the hilt.

- Menuki: A final, decorative charm that is wrapped into the ito. It covers the mekugi.

At the top of the tsuka, is a cap that ends the hilt called a kashira. On the other end of the blade lie the tsuba and the habaki. The tsuba is the guard of the sword and the habaki is the metal collar right underneath it that keeps the katana firmly sheathed.

Major Parts of the Tachi Koshira

There are several variations of tachi koshirae. The above is a Ito Maki tachi. Tachi are commonly associated with early Koto era swords and were worn by higher ranking samurai and daimyo. The tachi is worn edge down with the saya suspended from a sword belt. Tachi of various styles have been made from the earliest Koto eras through the modern period.

The Kazari tachi was one of the earliest styles of Japanese sword. It had a straight kiri-ha zukuri blade. This style of tachi was used in the early Koto period, Nara and Heian eras, and was worn only by nobles of the Imperial court.

Efu tachi, also called Hoso tachi, were likewise only worn by the highest ranking daimyo and officials of the court. Efu tachi have a shitogi tsuba. These are generally considered ceremonial mountings rather than combat mountings. Efu (Hoso) tachi were made from Koto through Showa times.

Bird’s Head Tachi is a variation of the Efu tachi and were carried as court swords during many periods of Japanese history. They were still being made as presentation swords during the Showa era.

There are also “hybrid” mountings called handachi which are similar to the buke-zukuri style but have kabuto-gane, sayajiri and semegane like a tachi. Handachi are worn edge up like buke-zukuri mounted blades.

Major Parts of a Shirasaya

A shirasaya is a storage scabbard used to protect the sword blade when not in use and when not mounted in its normal buke-zukuri or tachi fittings. The shirasaya is normally made of ho wood and may have information about the sword blade written on it (sayagaki).

Japanese Sword Mountings

From: http://www.japaneseswordindex.com/mounts.htm

It has been said that the Japanese sword was the soul of the Samurai. If this is indeed the case then, undeniably, the blade is also the soul of the Japanese sword. All other parts may be considered as secondary to the blade, but on a well mounted sword, the fittings compliment, enhance it and allow the blade to be actually used. A full set of mounts, not including the blade, is known as the Koshirae. The individual constituents of the Koshirae, which include Kodogu (metal mountings)Tsuka and Tsukamaki (hilt and hilt wrap) the Habaki and the lacquering and construction of the Saya (scabbard) are all collaborations between different artist and artisans with their individual specialities, whilst the Katana Kaji (swordsmith) and Togishi (polisher) work on the blade itself. These notes will briefly describe the various types of Koshirae some of which are dictated by the size of the blade.

Daito (long swords)

Uichigatana Koshirae: The Daito may come in a number of different types of Koshirae, regardless of the what type of blade it may be (Tachi or Katana). Of these, probably the most familiar is the Uichigatana or Katana Koshirae. This, if you like, is the definitive “Samurai sword”. Usually, the Saya will have no metal mounts but an infinite variety of lacquers may be used to decorate it. The lacquer has the added advantage of being resistant to water or damp and so, as in many Japanese art forms, it has a practical as well as decorative function. The Saya will also have a Kurigata (retaining “hook”) on the Omote side (which is sometimes metal) and is worn tucked through the Obi with the cutting edge uppermost, familiar to all practitioners of Iaido. The Koshirae will be complete with a Tsuba and Tsuka which will have Fuchigashira and Menuki, variously decorated.

Tachi Koshiarae: Unlike the Katana described above. The Tachi was worn with the cutting edge down and was originally an ancient style designed for combat whilst mounted on horseback. The Tachi’s Saya will have metal mounts (various rings, a chape and hanging devices) the design or decoration of which, is usually repeated on the Tsuba and Tsuka. Frequently the top 1/ 3rd of the Saya will be wrapped in the same manner as the Tsuka and this Koshirae is known as Ito-maki Tachi Koshirae (thread wrapped). Most extant examples of this style would have been for formal dress during the Edo period but there are 20th century examples around, usually with brass mountings and of lower quality.

Han-dachi Koshirae: A style of Koshirae which is a mixture of both the Uichigatana and Tachi Koshirae, is known as Han-dachi (half Tachi). Very popular during the Bakamatsu (end of the Edo period) this is worn in the style of Katana and not Tachi, but would retain a number of the metal Saya mounts and would also have a Kurigata.

Chisai-Katana: As the name implies (small Katana) this Koshirae differs only from the regular Katana by virtue of its size. Although some are said to have been made for one handed combat (Katate-mono) many were also made for the affluent merchant class who were subject to restrictions on the size of weapons they were allowed to wear. Such swords are often very richly mounted and the Sayas are ornately lacquered reflecting the ostentatious and wealthy nature of their owners, which contrasted to the more subdued (ideally) and restrained taste of the Samurai class.

Shoto (short swords and daggers)

Wakizashi-Koshirae: The Wakizashi was designed as the Shoto that accompanied the Daito in the matched pair of swords known as the Daisho (Daito + Shoto = Daisho). The two blades of a Daisho might occasionally be by the same maker, but the Koshirae would always be an obvious, though not necessarily exact, matched pair. Often Daisho have been split up and it is a collector’s dream to reunite the two swords of a Daisho (I have done this). Slots to accommodate the small Ko-gatana (auxiliary knife) or Kogai (a kind of skewer) are often found near the top of the Wakizashi’s Saya and, rarely, these may also be found on Katana-koshirae. The Wakizashikoshirae, therefore, is only different to the Katana or Han-dachi Koshirae, by virtue of size.

Tanto-koshirae: The Tanto or dagger might be worn as part of a Daisho instead of the Wakizashi, in which case the mounts would be in sympathy with those of the Daito. There are three basic types of Tanto Koshirae which might all contain similar types of blades.

- Tanto: with a normally formed (but obviously smaller) Tsuba, all the normal Tsuka mounts and a lacquered Saya. They might also accommodate the Kogatana in the same manner as a Wakizashi.

- Hamidashi Tanto: similar to the above but often slimmer overall and with a Tsuba that has most of one side cut away usually to make room for the top of the Kogatana.

- Aikuchi Tanto: with no Tsuba at all, the Fuchi is flush with the Koi-guchi and the name means “close fitting mouth”. Very often the Tsuka will have no Itomaki (thread wrapping) and the Menuki will be fixed directly onto the Same which covers the Tsuka. This style was originally designed for wearing with armour.

Shira-Saya

Finally, all lengths of swords might be found in Shira-saya. This is a storage rather than a practical mount and is plain, undecorated wood. In olden days a rich Daimyo or Samurai might have several different sets of Koshirae for one blade and would keep it in a Shira-saya when not being used (the Koshirae would be kept with a wooden blade, known as Tsunagi). The Shira-saya is undecorated except that sometimes an appraiser may brush an attribution onto the Saya.

Nowadays, when a sword is sent off for polishing, it will be returned in Shira-saya and if it has a Koshirae a Tsunagi would be made for it. Sadly, it is not possible in this situation, to return the blade to the Koshirae which may have traces of dirt that will damage the polish. A good Shira-saya also has the advantage of being almost airtight, limiting the blade’s exposure to dampness and lowering the risk of it rusting.

The above are the most commonly encountered Koshirae. I have omitted the Tachi variations such as Efu-no-tachi and Hoho-no-tachi as well as the Shin-gunto or modern army sword, which is modelled on the Tachi anyway. These are unlikely to be encountered by the average Kendo or Iaido student.

Koshirae: Nihon Token Gaiso (The Mountings of Japanese Swords)

by C. U. Guido Schiller (January 2000)

From: http://www.japaneseswordindex.com/koshirae/koshirae.htm

A Brief History of the Development of Koshirae

Koshirae derives from the verb “koshirareru”, which is no longer in use nowadays. Usually “tsukuru” is used instead; both mean “make, create, manufacture”. More accurate is actually “Toso”, which means sword-furniture: “Tosogu” are the parts of the mounting in general, and “Kanagu” stands for those made of metal. “Gaiso” are the “outer” mountings, as opposed to “Toshin”, the “body” of the sword.

Nihonto are classified by length and koshirae and the combination of both. Swords over 2 shaku (1 shaku = 30.3 cm, or about 1 foot) from tip to munemachi (notch where the tang starts) are daito, from 1 to 2 shaku are shoto, and under 1 shaku are tanto. The usual daito are the katana and tachi; shoto are mostly wakizashi, and there is an infinite variety of tanto. Borderline cases are kodachi (tachi shorter than 2 shaku) and O-wakizashi (wakizashi of *almost* 2 shaku). Women used to carry a tanto in the Edo period in a “brocade bag” in their obi; this tanto for self-defense was called kaiken.

The first swords made of steel were imported from China, and had Chinese mountings. The koshirae prototypes of purely Japanese design developed during the Nara period (646 ~ 794 AD), although they were still called “Kara-tachi”, i.e. Chinese tachi. Only a few survived time, but there seemed to have been two types: swords in black lacquered wooden mountings for actual combat, and those richly decorated with semi-precious stones and fancy lacquering. Rayskin was used on the handles from time to time, but only became common during the Heian period (794 ~ 1185 AD). Swords of that time were called “Kazari-tachi” (decorative tachi) or “Hoso-tachi” (narrow tachi), already adjusting in blade construction to Japanese taste and usage. They were luxuriously mounted, and meant for use by the palace guard at the imperial court. Later on they became a little bit simpler with a “Shitogi-tsuba” (rice cake tsuba), renamed “Efu-tachi”, and were still in use during the Edo period by imperial guards and high ranking officials.

Another interesting sword is the “Kenukigata-tachi” (hairpin tachi), and there is much speculation about its usefulness. Since it has a forged handle, it must have been pretty tiresome to use, although there are some examples with battlemarks. But it is believed that it served mostly decorative purposes, or as presents to shrines to celebrate a happy occasion. Most fighting swords were pretty sombre with mountings in black lacquer or covered with leather (Kawazutsumi-tachi). At the end of the Heian period and the following Kamakura period (1185 ~ 1336 AD), the “Hyogo-Kusari-tachi” was very popular. It was named after the chain-hangers, and usually was covered with metal foil.

The first “Itomaki-no-tachi” were used in the Nambokucho period (1336 ~ 1392 AD). They had tsukamaki as well as sayamaki, i.e. there was wrapping at the upper part of the saya to prevent damage from rubbing against the armor. The itomaki-tachi became the tachi of choice for the following centuries for use in battle. Sometimes the lower part of the saya had a cover made of fur to protect it from the elements, which was called “shirizaya” (butt saya).

Although the “uchigatana” (lit. “strike-sword”) already had its predecessors in the Heian period, it became standard for foot soldiers during the Nambokucho period. Unlike the tachi, which was carried edge down, and had two obitori (hangers) on the saya, the uchigatana is worn through the sash, edge up.

Tachi were still produced during the Muromachi period (1392 ~ 1573 AD), but the uchigatana became the most common daito. Kanagu other than the tsuba, up until now made from yamagane (“mountain metal”, unrefined copper), was often made from shakudo, copper with 5% gold, patinated a deep black. Uchigatana still looked very much like tachi except for the obitori, and therefore were called “handachi”, half-tachi; this style never really went out of fashion during the next 300 years.

Since the early Muromachi period, the manufacture of tsuba became a separate profession; until then, tsuba were forged by swordsmiths, armorsmiths or Kagamishi, mirror smiths (polished disks of metal were used as mirrors). Early tsuba had sukashi, cut-outs in negative silhouette, but from now on brass inlays and positive silhouette sukashi, especially from Owari province, became more refined. The Shoami family became one of the main manufacturers of tsuba, with many generations to follow.

The Momoyama period (1573 ~ 1603 AD) is well known for its flamboyant koshirae with red lacquered saya and kanagu in gold. Those flashy mountings however were counterbalanced by Tensho-Koshirae (era name of emperor Tensho, 1573 ~ 1586 AD) with black saya and same’, a tapered tsuka with leather binding crossed over a kashira made of horn.

Part of the tsubashi from Kyoto moved to Akasaka in Edo, and produced many fine sukashi tsuba. The Myochin family switched from manufacturing armor to making tsuba. Echizen province tsuba were dominated by the families Akao, Nagasone and Kinai; the Kinai had from their second generation on a special relationship with Echizen Yasutsugu, the Shogun’s favorite smith. They not only carved the dragon horimono for his swords, but also the Aoi-no-Gomon, the family crest of the Tokugawa, on the tang of his swords. Both motifs are also very often found on their tsuba.

In Higo province the tosogushi were encouraged by the Hosokawa Daimyo, and worked in iron, copper, brass and cloisonne. The characteristics of Higo koshirae are the rounded kashira and kojiri; the same’ is often black, and the saya in samenuri – the “valleys” in the same’ filled with lacquer, and the “mountains” polished flush. Tsuka had often a leather wrapping. This kind of koshirae was later copied as “Edo-Higo-Koshirae”, but mostly with simpler saya and natural colored same’.

After Tokugawa Ieyasu moved to Edo, many artists set up their workshop there. In the Edo period (1603 ~ 1868 AD) the Goto family, which already had worked for the Ashikaga, almost dominated sword fittings, especially for the daisho. This combination of katana and wakizashi became the standard for samurai during the Momoyama period.

As with many other things, wearing of swords was regulated. For example, in Genna 9 (1624 AD), red saya, swords over 2 shaku and square tsuba were prohibited. Commoners weren’t allowed to wear swords at all.

Samurai at the castle in Edo wore the Banzashi daisho, “duty attire”. Same’ had to be white, the saya black lacquered and with horn fittings. The kojiri of the katana was flat, and that of the wakizashi rounded. The kashira had to be horn, with the black tsukamaki crossed over it (kakemaki). The fuchi and midokoromono (“things of the three places”: menuki, kogai and kozuka) had to be shakudo-nanako (fish-roe pattern) with the only decoration being the family mon (crest). The tsuba was polished shakudo without any decoration. However, this was not always strictly enforced, and kanagu with shishi (lion dogs), dragons or floral motifs were tolerated.

Samurai had to wear the “Kamishimozashi” when on official duty, with the “Kataginu” wing shoulders and “Hakama” split skirt trousers, while Kuge (court nobles), Daimyo and other high ranking officials were clad in the Hitatare court attire with Eboshi-hat, with a wakizashi at their hip. This was either an aikuchi (“meeting mouth”, i.e. without tsuba) or hamidashi (a very small tsuba) in dashizame, or hilt covered in same’ without tsukamaki. This short sword didn’t have a mekugi to fasten the hilt to the tang, which rendered it impractical, because the wearer wanted to show that – due to his high rank – he didn’t have to use it anyhow. Besides, it was a serious offense to draw a sword at court, as anybody who read or watched “Chushingura“, the 47 Ronin, would know.

Bronze, copper and brass were widely used with “regular” swords, as well as the alloy shibuichi (“one quarter”, 75% copper and 25% silver) Those soft metals were called “kinko” (gold/precious metal work) as opposed to iron mountings. Pure silver mountings are quite rare, as are pure gold mountings, which were banned in 1830.

Yokoya Somin left the Goto school, which only worked with shakudo, and invented “katakiribori”, engravings with a triangular chisel. In Nara, the Nara-Sansaku (“three makers from Nara”) (Nara Toshinaga, Sugiura Joi, and Tsuchiya Yasuchika) became famous with sunken relief.

Yagyu tsuba developed from Owari tsuba, so called after the Yagyu family, fencing instructors for the Shogun. Typical Yagyu koshirae has a ribbed saya, and the menuki are at reversed positions of regular menuki placement.

At home samurai put their daisho on a double-rack, edge up, katana on top, tsuka to the left. Actually they were greeted at the entrance of the house by their wives, who carried the swords after pulling the sleeves of their kimono over their hands in order to not touch the swords with their bare skin. They then put a tanto into their sash, which was not subject to any restrictions, and was often lavishly decorated.

Although commoners weren’t allowed to carry any swords, some of them, especially rich merchants, showed off their wealth by sporting expensive tanto, walking a very thin line between status symbol and severe punishment. Physicians wore tanto made of solid wood, and firefighters sometimes had a tanto with a saw instead of a blade.

On July 18, Shoho 2 (1645 AD), the ban of wearing swords was reduced to swords over 1.8 shaku, if one obtained a permit. This enabled travelers on the Tokaido road to arm themselves against robbers which were encountered quite frequently in unpopulated areas, and also enabled the chief of police of Edo to arm the “Okappiki”, non-samurai police.

The end of the Edo period is called “Bakumatsu”, and brought many changes to the samurai class. Some already tried western clothes, and wore “Toppei koshirae” swords, also called zubon (trousers) koshirae, which had no tsukamaki and a softly rounded kojiri. In 1871 everybody was allowed to carry a sword or to wear their hair “Chonmage”, samurai topknot. Kirisute-gomen was prohibited, which was the unpunished slaying of a non-samurai for a (real or imagined) insult. But the Haitorei edict, which took effect on January 1, 1877, limited the right of carrying swords to the military and police. Most swords concealed in a cane or walking stick are made shortly after this edict.

Swords of the Meiji (1868 ~ 1912 AD) and Taisho (1912 ~ 1926 AD) period were fashioned after French and German military sabers, and only the gunto (military swords) after 1933 saw a renaissance of Japanese design.

Koshirae of Special Interest

Nodachi: During the Kamakura and Nambokucho period, tachi of extended length were sometimes used on the battlefield. Those swords certainly had an intimidating effect on the enemy, but their usefulness is highly questionable since they were very awkward to handle. Most were of very low quality.

Chiisagatana: Chiisagatana, lit. “short katana”, are shoto mounted as katana. Now, one could argue that wakizashi are shoto which are mounted in a similar way to katana, and that’s absolutely correct. But we’re talking here about the predecessors of the daisho, the formal katana/wakizashi pair. In the transitional period from tachi to katana, katana were called “uchigatana”, and shoto were referred to as “koshigatana” (hip-sword) and “chiisagatana”, in many cases quite longer than the later “standard” wakizashi.

One can’t make out the difference between wakizashi and chiisagatana by blade alone, although a Koto shoto close to 2 Shaku (like the above mentioned O-wakizashi) would be a good indication; it depends on the mountings. Chiisagatana are the early shoto type with koshirae not easily distinguishable from the uchigatana, just shorter, but in any case with a tsuba (another term for chiisagatana is “tsubagatana”, “sword with tsuba”, as opposed to aikuchi). The ban of carrying swords for non-Samurai wasn’t in effect yet, so people from all runs of life, who preferred shorter blades, would have chosen the chiisagatana/ koshigatana/ O-wakizashi/ tsubagatana.

Daisho: As already mentioned, a daisho (lit. “big/small”) is the katana/wakizashi or katana/tanto pair that was one of the outer attributes of the samurai. Most daisho were mounted en suite, but actually any combination of a short and a long sword is considered a daisho; and it is either a wakizashi or a tanto together with the katana, never both.

Ninjato: Actually, there is no such thing as a special purpose ninja sword, although Hollywood and Toei filmstudios want to make us believe that. But neither ninja nor “Onmitsu Doshin”, the undercover agents of the Edo police, had a “standard” short sword with a straight blade, square tsuba and black fittings.

Present day SWAT teams and military commandos use special or modified weapons to suit their task, and so did assassins and spies of the Edo period. A shorter sword slung over the back might have proven useful for penetrating a castle and combat in confined spaces, but different situations would have called for a different sword. “Ninjato” has a nice ring to it, but the “sword shopping guide for spies” has yet to be discovered …

General Remarks on Koshirae and Placement of Fittings

When restoring an antique sword, or mounting a newly made shinsakuto for the first time, it is often difficult to make a choice in regard to the style and color of the tsukamaki, the saya, and the proper placement of the fittings. Although it’s basically a matter of personal taste, there are a few rules concerning selection and placement of koshirae.

Generally speaking, “up” and “front” of fittings would be as viewed from the side, or the tip of the tsuka, when the sword is held horizontally, sword edge down in case of a tachi and edge up for any other sword/dagger.

Tsuka: There are four basic shapes of tsuka:

- 1. “Haichi Tsuka”, the most common, the mune-side almost straight, the ha-side slightly tapered, following the lines of the sword

- “Rikko Tsuka”, almost hour glass shaped

- “Imogata” (“potatoe shape”), both sides straight

- “Morozori”, closely following the shape of the saya, mostly with tachi/ handachi

The length of the tsuka was usually tailored to the individual swordsman’s specifications. As a rule of thumb, the length of the handle of a katana is twice the width of the hand plus two fingers, the wakizashi 1.5 hand widths and the tanto one hand width. Average length of a katana tsuka used to be 8 sun (24 cm or 9.5 inches).

Tsukamaki: It is not historically proven, but traditional Kabuki and Chambarra (period movies) indicate the rank of a samurai by the color of the tsukamaki: black – blue – dark brown – light brown – gray – purple – white. However, since this approximates roughly the percentage of colors found on swords, it might be about right.

The most common wrapping method is “Tsumamimaki”, the ito “pinched” at the crossing, followed by “Hinerimaki”, where the ito was folded over twice at a 90 degree angle at the crossing. Tachi were usually done in “Hiramaki”, the ito simply crossed over.

Mekugi: The Mekugi is made from seasoned bamboo, convex shaped, and inserted from the side of the tsuka that is covered by the palm. Bamboo is strong yet elastic, and even if the mekugi breaks, the tough fibers will prevent the blade from slipping out of the handle. Sometimes horn or metal was used instead of bamboo, but usually not on swords intended for fighting.

Menuki: Menuki were originally used to cover the mekugi pin that fastens the handle to the tang. Later on they became purely ornamental, and were placed about one hands width from the fuchi on the omote (outward side) and the kashira on the ura (side facing the body) on tachi. However, when the uchigatana was “invented”, the placement wasn’t changed for traditional reasons, although the sword was now worn edge up and in effect resulted in a reversed position of the menuki.

An additional benefit of the menuki placement of tachi was the better grip on the tsuka, since the menuki filled the gap in the palm of the hand. But “Gyaku-Menuki”, or “anatomically correctly” placed menuki were almost only used on Yagyu koshirae.

That menuki became more or less decorative elements of the tsuka is evident on tanto (and to a lesser degree on wakizashi). On the short handle of a tanto they were almost opposite of each other, and sometimes even omitted.

Tsuba: Sometimes it might be difficult to determine the front (i.e. facing away from the body) and back side of a tsuba. If the tsuba has a kozuka hitsu or kogai hitsu (slots for kozuka and kogai), the one for the kozuka is always to the left and the one for the kogai always to the right. The mei (inscription) of the maker is usually on the front, but there are sometimes exceptions. In most cases the more decorated side is the front side. If it is an undecorated tsuba, or a sukashi tsuba, without any slots, the side showing more wear is probably the front.

The average diameter of a katana tsuba, measured at the widest part, seldomly exceeds about 7.5 cm or 3 inches.

Bibliography

Although there are countless books on swords and sword fittings, only a very few were published on Koshirae, and to my knowledge not a single one in English. The following books are Zukan (“illustrated books”), with many photographs of Koshirae:

A classic is “Zukan: Toso no Subete” by Kokubo Kenichi. In Japanese, but with many Furigana (Kana readings of the Kanji), price used to be Yen 2,300, but now out of print.

A pretty recent publication is “Toso-Hen“, a book in a series on artwork of the Tokyo National Museum (English title: Illustrated Catalogue of Tokyo National Museum – Sword Mountings). In Japanese, but with an English list of the plates, Yen 5,238.

Almost an encyclopedia of the Japanese sword and its mountings is “Zukan: Nihonto Yogo Jiten“, which has a supplement “Nihonto: Swords of Japan, a Visual Glossary” with English translations. Published privately by the author Kotoken Kajihara, Yen 35,000

(For buying books on Japanese (and other Asian) art, I recommend the “Paragon Book Gallery” in Chicago. Good selection, reasonable prices, fast and friendly service. They have a very good website with online store: www.paragonbook.com)

Japanese Sword Flaws (Kizu)

There are numerous types of flaws (kizu) which can be found in Japanese sword blades. All detract from the artistic beauty of the blade and many render the blade non-functional and/or valueless. With the exception of broken or cracked kissaki (points), the following types of kizu can be found anywhere on the sword blade. Non-fatal flaws can be corrected by an experienced polisher whereas fatal flaws cannot be corrected and render the blade completely non-functional and generally of little or no value. It should be noted that even fatal flaws may be acceptable in a really old blade (early Kamakura Period) and/or in blades by noted smiths. An experienced collector/student of Nihonto must decide what is acceptable for their collection. While a blade may be seriously flawed and have little monetary value, it may still be a useful study piece to aid in learning the characteristics of particular smiths or schools of swordsmiths.

Examples of Kizu

Broken Kissaki – This is a fatal flaw if the kissaki has been broken past the boshi (tempered area). If the break does not extend past the boshi, a good polisher may be able to reshape the kissaki.

Chips – in the ha (edge) or kissaki (point) may or may not be fatal depending on whether they extend thru the hamon (tempered edge) or boshi (tempered point). A fatal flaw if chip extends past the hamon.

Fukure – Air or carbon pockets or blisters in the steel. Normally due to a bad weld between layers when blade was forged.

Hagire – Cracks in the hamon (tempered edge) perpendicular to the edge. These are commonly VERY difficult to see, especially under poor lighting conditions. Hagire are fatal flaws.

Ji-Are – Irregular or raised area; may be indicative of underlying blister or core steel being exposed due to excessive polishing.

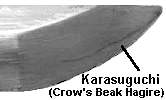

Karasuguchi – (Crow’s Beak Hagire) – Crack in the boshi. These are fatal flaws.

Shinae – Ripples or wrinkles in the skin steel generally due to a bent blade having been straightened. These can be anywhere on the blade (shinogi-ji, mune, etc).

Umegane – Region of blade filled with separate piece of steel; generally to fill in a major carbon or air pocket.

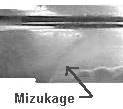

Mizukage – Cloudly line running diagonally from the ha (edge) near the ha-machi. This is commonly a sign that the blade has been retempered. While there were a few smiths that made mizukage deliberately, most often it is considered a flaw and indicator of a retempered blade. On retempered blades the hamon will sometimes stop in front of the ha-machi. Again, some smiths did this deliberately, but most commonly it is a sign of a retempered blade.

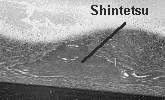

Shintetsu – Dark areas on the surface of the blade (ji or shinogi-ji) where the outer layer of steel has been removed and core steel shows through. This is normally a result of over polishing and indicates a “tired” blade.

Ware – Horizontal “lines” (splits) generally due to a poor weld between layers of steel. Ware may occur anywhere on the blade (mune-ware, tate-ware, shinogi-ware, etc). These are very common.

Nioi Gire (interrupted hamon) – If the hamon (temperline) is interrupted or runs off the blade at any point, or off the boshi; it is a major, normally fatal flaw.

There are numerous other types of defects/flaws found in Japanese sword blades. Be certain to check CAREFULLY when examining a blade prior to purchase. Many flaws are quite subtle and can be very difficult to see (especially hagire – use a magnifying glass). Also be sure to sight down the back (mune) of the blade from the nakago (tang) to the kissaki (point) to determine if the blade is bent. Take your time when examining a blade as once the blade is purchased it is too late to complain about a newly found flaw.

How to Recognise a Good Sword

From: http://www.japaneseswordindex.com/gdsword.htm

By Clive Sinclaire – Chairman, Token Society of Great Britain

Since I started writing a few short essays for B.K.A. News, I have been asked, by one or two members, my opinion on their swords. Sometimes I have been horrified by what I have seen but occasionally I have been pleasantly surprised. However, in both instances it has been apparent that, even if the owner treasured the piece in question, he or she would not know really what they possessed. This has prompted me to jot down these few notes to try and give a few checkpoints when looking at a blade and to help avoid the worst pitfalls when considering acquiring a Japanese sword.

The close study of Japanese swords is a highly time consuming and difficult process (although highly rewarding) and so these brief notes can be no more than a very rough guide to sword appraisal. Further many of the points are highly subjective and it is a great start if you already have a basis of having seen good swords. In other words, if you have seen the best then you have a bench-mark for judging the rest.

There is a reasonably logical procedure for examining a Japanese sword blade and this is used in the practice of Kantei Nyusatsu. In Kantei sessions, a blade is presented to a participant with any inscription there might be on the Nakago covered and the maker’s name must then be guessed. If the procedures are followed, this apparently daunting task may be accomplished with less difficulty than might be expected. The procedure for Kantei, is as follows:

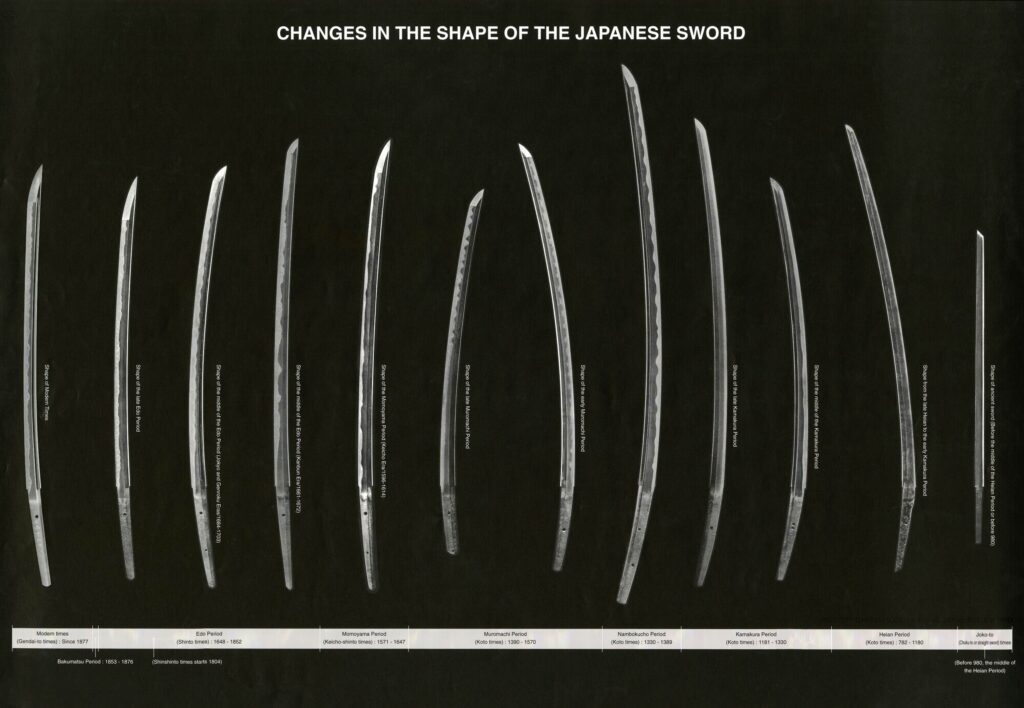

1) First the Sugata or shape of the blade must be examined. The shape should appear strong, the curvature natural and the Kissaki should be in proportion to the width and length of the blade. The Mune or back edge’s shape and height should also be noted. When examining a blade’s Sugata, the blade is best held upright at arm’s length.

In fact the Sugata may impart a great deal of information about the age of the blade and sometimes about the area in which it was made. However, if the blade has a good shape and sits comfortably in the hand, there is a fair chance that it has some quality. It is impossible for a good sword to have a bad shape unless it has been altered, damaged or repaired in some way. This frequently happens and so it is important to try and imagine the Ubu (unaltered) shape of the blade.

2) The next area to study is the Hamon. This is often referred to as the ‘tempered’ edge. This is where the sword has been quenched to provide a high carbon steel area which will hold a sharpened edge. It will be seen in contrast to the body of the sword.

The Hamon may be in an infinite variety of patterns, but appears as a milky white colour on a properly polished blade. The upper edge of the Hamon will be formed from tiny martensite crystals called Nie. Sometimes these are too small to see with the naked eye and are then known as Nioi. It is Me and Nioi that border the Hamon and form the pattern of the Hamon and they should be examined very closely, ideally by holding the blade at eye level, ideally pointed towards a spotlight. The Nioi- guchi (line of the Hamon) should form an unbroken and constant line from the Machi area (bottom of the blade) along its entire length. A break in the Hamon, called Nioi-giri is a serious flaw and should be avoided. It is also important that the Boshi (the area of the Hamon within the Kissaki) does not disappear off the edge. This is also a serious flaw in the blade and is only acceptable on great swords of historical and cultural significance! No compromise should be accepted here.

3) If Sugata and Hamon pass muster, the sword should be OK. However, we need to assure ourselves that it is hand forged and not a cleverly mass-produced piece such as a Showato (mass produced during World War 2). This is ascertained by examining both the Jigane and Jihada. The Jigane is the actual steel from which the sword is made and might show subtle change colour and texture whilst the Jihada is the surface pattern of the Jigane caused by the forging process and emphasised by the polishing. This is mostly visible between the edge of the Hamon and the Shinogi or ridge line. The Jihada, appearing like a wood grain, is described by its type and size (i.e. Ko-mokume small burl) and there are many criteria for judging the quality of the Jihada. However, for the purposes of this essay, I guess that it is sufficient to say that if Jihada is present, then the sword is at least a hand forged blade.

4) Whilst undertaking this detailed examination of a blade, any flaws or faults will become apparent. Some of these may be more acceptable than others, dependent on the age of the blade. In other words, a 12th century blade is entitled to have a few problems that would not be tolerated in a modern sword. However, all faults and flaws obviously detract from both the beauty and value of a sword.

Look for holes or bubbles in the sword which may indicate air or impurities that have been included in the forging process and may be just under the surface of the blade. Also check the Ha-saki (cutting edge) very carefully for hairline vertical cracks running from the Ha-saki into the Hamon. Called Ha-giri, these are very serious flaws as if the sword were used to cut, at the point of Ha-giri it would bend or break. Ha-giri is not acceptable under any circumstance.

5) Finally inspection of the Nakago or tang takes place. The Nakago on a good sword will always be carefully finished. The patination should be a good colour and the rust should not be cleaned off under any circumstances. If there are any inscriptions these will be of interest. A good Mei will be skilfully and confidently written, not untidy, jumbled or hesitant. It almost does not matter whether you can read the inscription (most modern Japanese cannot read the old Kanji in sword inscriptions) so long as it looks confidently executed.

You will understand from the above what I mean by there are many subjective judgements to be made when judging a Japanese sword blade. There are many other subtle details in both Jihada and Hamon (known as Hataraki or activities) which add enormously to the beauty of the Japanese sword, however, detailed explanation of these are not really within the scope of this short essay.

Finally I would make a couple of points which may prevent you making a costly mistake. The most commonly encountered swords in the West are the previously referred to, Showa-to. These blades were made in the Showa period (1926-89) and the vast majority were mass-produced for the Imperial Army and Navy during the Pacific War period. These swords are not considered as true Nihon-to and as they are seen as symbolising Japan’s recent militaristic past they are still illegal in Japan. Showa-to are reasonably easy to recognise from their small stamps on the Nakago (usually Seki or Showa) and often they are signed with untidy and loosely carved characters. Often an unsharpened inch or so of blade (known as Ubu-ha) is found just above the Habaki and these heavy and clumsy swords are usually found in Gunto (army) mounts. Mostly they appeal to militaria collectors and I do not think they are suitable for Iai practice or the serious study of Japanese art swords.

Having said this, I would point out that during the Showa period there were some highly talented swordsmiths working producing very fine blades indeed. There are also a minority of blades found in Gunto mountings that are fine old ‘family’ blades that were traditionally made. Maybe we’ll discuss these in a later issue of B.K.A. News.

Meanwhile, should any member have any questions on an aspect of Japanese swords, I would be happy to attempt to answer them.

Sword Blade Terminology

From: http://www.japaneseswordindex.com/terms/terms.htm

The graphics used in this section are adapted from ToShow 6, a Japanese sword database program written by Peter McCollum, and are used with his permission.

General Shapes of Sword Blades, Mune, Kissaki

There are a variety of shapes of Japanese sword blades, kissaki (points) and blade backs (mune). Some of the most common of shown below.

Boshi

The boshi is the tempered part of the sword point (kissaki). Some of the more common styles of boshi are:

Hada

The hada is the visible design of the grain of the sword steel. It is a result of the way the sword was folded during forging. Hada can be difficult for the beginner to interpret and it is easily obscured by a poorly polished blade or one which is stained or rusted.

Hamon

The hamon is the design of the tempered edge of the sword blade. It is a result of the differential cooling of the blade (quenching and tempering) after it is forged. There are numerous styles of hamon and quite commonly mixed styles such as choji-midare or midare-togari. Some of the major forms are shown below.

Hataraki

“Hataraki” or “activities” or “workings” in the hamon are various types of lines, streaks, dots and patches which result from the interaction of the steel during the quenching process. “Ashi” means “legs” which are streaks of nioi extending toward the ha (edge); “ko-nie” are small dots of nie above the hamon; “ji-nie” are patches of nie in the ji; “sunagashi“, “kinsuji” and “inazuma” are streaks within and above the hamon; “uchinoke” are cresent shaped areas. “Chikei” are running dark lines in the ji. A proper polish is required for the activities in the hamon to be well visualized. An active hamon is normally the mark of a better quality blade. Activities are not usually seen in bar stock, oil quenched WW II era gunto blades.

Shapes of Sword Tangs

Nakago

There are a variety of shapes of Japanese sword tangs (nakago). Some of the most common of shown below.

Shapes of Tang Tips: Nakago-Jiri

The “kurijiri” is a rounded tang tip; “haagari” is asymmetrcally round; the “kiri” is a square cut tip; “kengyo” is symmetrically pointed; “iriyamagate(katayama)” is asymmetrically pointed. Most tangs which are “suriage” (cut off or shortened) will have “kiri” nakago-jiri.

Styles of Tang File Marks: Yasurime

Japanese Sword Glossary

From: http://www.japaneseswordindex.com/glossry.htm

AIKUCHI – a tanto with no tsuba (guard)

AOI – hollyhock, commonly used as a Mon

ARA-NIE – coarse or large nie

ASHI – legs (streaks of nioi pointing down toward the edge)

ATOBORI – horimono added at a later date

ATO MEI – signature added at a later date

AYASUGI – large wavey hada (grain)

BAKUFU – military government of the Shogun

BO-HI – large or wide groove

BOKKEN – wooden sword for practicing sword kata

BONJI – sanskrit carvings

BO-UTSURI – faint utsuri

BOSHI – temper line in kissaki (point)

BU – Japanese measurement (approx 0.1 inch)

BUKE – military man, samurai

BUSHIDO -the code of the samura

CHIKEI – dark lines that appear in the ji

CHISA KATANA – short katana

CHOJI – clove shaped hamon

CHOJI OIL – oil for the care of swords

CHOJI-MIDARE – irregular choji hamon (temper line)

CHOKUTO – prehistoric straight swords

CHU – medium

CHU-KISSAKI – medium sized point (kissaki)

CHU-SUGUHA straight, medium width temper line

DAI – great or large

DAI-MEI – student smith signing his teacher’s name

DAIMYO – feudal lord

DAISHO – a matched pair of long and short swords

DAITO – long sword (over 24 inches)

FUCHI – collar on hilt

FUCHI-KASHIRA – set of hilt collar (fuchi) and buttcap (kashira)

FUKURA – curve of the ha or edge in the kissaki (point)

FUKURE – flaw; usually a blister in the steel

FUKURIN – rim cover of a tsuba

FUNAGATA – ship bottom shaped nakago

FUNBARI / FUMBARI – much taper of the blade from the machi to the kissaki

FURISODE – shape of sword tang that resembling the sleeve of a kimono

GAKU-MEI – original signature inlaid in a cut-off (o-suriage) tang

GENDAITO – traditionally forged sword blades by modern smiths

GIMEI – fake signature (mei)

GIN – silver

GOKADEN – the Five Schools of the Koto period

GOMABASHI – parallel grooves

GUNOME – undulating hamon

GUNOME-MIDARE – irregularly undulating hamon

GUNTO – army or military sword mountings

GYAKU – angled back, reversed

HA – cutting edge

HABAKI – blade collar

HABUCHI – the line of the hamon

HADA – grain in steel, pattern of folding the steel

HAGANE – steel

HAGIRE -edge cracks in the hamon (fatal flaw)

HAKIKAKE -broom swept portions in the boshi

HAKO BA – box shaped hamon

HAKO-MIDARE – uneven box shaped hamon

HAKO-MUNE – square shaped blade back

HAMACHI – notch at the beginning of the cutting edge

HAMIDASHI – tanto or dagger with a small guard (tsuba)

HAMON – temper pattern along blade edge

HANDACHI – tachi mountings used on a katana or wakizashi

HATARAKI – activities or workings within the hamon or temperline

HAZUYA – finger stones used to show the hamon and hada

HI – grooves in the blade

HIRA-MUNE – flat blade backridge

HIRA-TSUKURI / HIRA-ZUKURI – blade without a shinogi (flat blade)

HIRO-SUGUHA – wide, straight temper line (hamon)

HITATSURA – full tempered hamon

HITSU / HITSU-ANA – holes in the tsuba for the kozuka or kogai

HO – kozuka blade HONAMI – family of sword appraissers

HORIMONO – arvings on sword blades

HOTSURE – stray lines from hamon into the ji

ICHI – one or first

ICHIMAI – one-piece sword construction

ICHIMAI BOSHI – point area (kissaki) that is fully tempered

IHORI-MUNE – peaked back ridge

IKUBI – boar’s neck (a short, wide kissaki)

INAZUMA – lightning (a type of activity in the hamon)

ITAME – wood grained hada

ITO – silk or cotton hilt wrapping

ITOMAKI NO TACHI – tachi with top of saya wrapped with ito

ITO SUGU – thin, thread like hamon

JI – sword surface between the shinogi and the hamon

JI-GANE – surface steel

JI-HADA – surface pattern of the hada

JINDACHI – tachi

JI-NIE – islands of nie in the ji

JIZO BOSHI – boshi shaped like a priest’s head

JUMONJI YARI – a yari with cross pieces

JUYO TOKEN – highly important origami for sword by NBTHK

JUZU – hamon like rosary beads

KABUTO – helmet

KABUTO-GANE – tachi style pommel cap

KABUTO-WARI – helmet breaker

KAEN – flame shaped boshi

KAERI – turnback (refers to the boshi at the mune)

KAI GUNTO – naval sword

KAJI – swordsmith

KAKIHAN – swordsmiths or tsuba makers monogram

KAKU-MUNE – square back ridge

KAMIKAZI – divine wind

KANJI – Japanese characters

KANMURI-OTOSHI – backridge beveled like a naginata

KANTEI – sword appraisal

KAO – carved monogram of swordsmith on tang (nakago)

KASANE – thickness of blade

KASHIRA – sword pommel or buttcap

KATAKIRI – sword with one side flat (no shinogi)

KATANA – sword worn in the obi, cutting edge up

KATANA KAKE – sword stand

KATANA-MEI – signature side that faces out when worn edge up

KAWAGANE – skin or surface steel

KAZU-UCHI MONO – mass produced swords

KEBORI – line carving done on sword mounts

KEN – straight double edged sword

KENGYO – triangular or pointed nakago-jiri

KESHO YASURIME – decorative file marks on nakago

KIJIMATA – pheasant thigh shaped nakago

KIJIMOMO – pheasant leg shaped nakago

KIKU – chrysanthemum

KIKUBA – chrysanthemum temperline (hamon)

KIN – gold

KINKO – soft metal sword fittings (not iron)

KIN-MEI – gold inlay or gold lacquer appraiser’s signature

KINZOGAN MEI – same a kin-mei

KINSUJI – golden line (type of activity in hamon)

KINZOGAN-MEI – attribution in gold inlay on nakago

KINSUJI – whitish line along hamon

KIRI – paulownia

KIRI HA – flat sword with both sides beveled to the edge

KIRI KOMI – sword cut or nick on the blade from another sword

KISSAKI – point of blade

KITAE – forging

KIZU – flaw

KO – old or small

KOBUSE – blade constructed with hard steel around a soft core

KO-CHOJI – small choji hamon

KODACHI – small tachi

KODOGU – all the sword fittings except the tsuba

KOGAI – hair pick accessory

KOIGUCHI – the mouth of the scabbard or its fitting

KOJIRI – end of the scabbard

KOKUHO – national treasure class sword

KO-MARU – small round boshi

KO-MIDARE – small irregular hamon

KO-MOKUME – small wood grain hada

KO-NIE – small or fine nie

KO-NIE DEKI – composed of small nie

KOSHIATE – leather suspensors (hangers) for a sword

KOSHIRAE – sword mountings or fittings

KOSHI-ZORI – curve of the blade is near the hilt

KOTO – Old Sword Period (prior to about 1596)

KOZUKA – handle of accessory knife

KUBIKIRI – small tanto for cutting the neck or removing heads

KUNI – province

KURIJIRI – rounded nakago jiri

KURIKARA – dragon horimono (engraving/carving)

KURIKATA – scabbard (saya) fitting for attaching the sageo

KUZURE – crumbling or disintegrating

KWAIKEN – short knife carried by womenMACHI – notches at the start of the ha and mune

MACHI-OKURI – blade shortened by moving up the ha-machi and mune-machi

MARU – round

MARU-DOME – round groove ending

MARU-MUNE – round mune

MASAME – straight grain (hada)

MEI – swordsmith’s signature

MEIBUTSU – famous sword

MEKUGI – sword peg

MEKUGI-ANA – hole for mekugi

MEMPO – face guard or mask

MENUKI – hilt ornamentsMIDARE – irregular, uneven temperline (hamon)

MIDARE-KOMI – uneven pattern in boshi

MIHABA – width of sword blade at the machi

MIMIGATA – ear shaped hamon

MITOKOROMONO – matching set of kozuka, kogai and menuki

MITSU KADO – point where yokote, shinogi and ko-shinogi meet

MITSU-MUNE – three-sided mune

MIZUKAGE – hazy line in ji commonly due to re-tempering

MOKKO – four lobe shaped (a tsuba shape)

MOKUME – burl like hada

MON – family crest

MONOUCHI – main cutting portion of blade (first six inches from kissaki)

MOROHA – double-edged sword

MOTO-HABA – blade width near habaki

MOTO-KASANE – blade thickness

MU – empty or nothing

MUJI – no visible grain

MUMEI – no signature (unsigned blade)

MUNE – back ridge of sword blade

MUNEMACHI – notch at start of mune

MUNEYAKI – regions of temper along the mune

MU-SORI – no curvature

N.B.T.H.K. – Nihon Bijutsu Token Hozon Kai (sword preservation group)

NAGAMAKI – halberd weapon mounted as a sword

NAGASA – blade length (from tip of kissaki to munemachi)

NAGINATA – halberd

NAKAGO – sword tang

NAMBAN TETSU – foreign steel

NANAKO – raised dimpling (fish roe)

NAOSHI – corrected or repaired

NASHIJI – hada like pear skin

NENGO – Japanese era

NIE – bright crystals in hamon or ji

NIE-DEKI – hamon done in nie

NIKU – meat (blade having lots of fullness)

NIOI – cloud like hamon

NIOI-DEKI – composed of nioi

NIOI-GIRE – break in hamon

NODACHI – large tachi worn by high officials

NOTARE – wave like hamon

NOTARE-MIDARE – irregular wave like hamon

N.T.H.K.. – Nihon Token Hozon Kai (sword appraisal group)

NUNOME – overlay metal-work

O – large

OBI – belt sash

O-CHOJI – large choji hamon

O-DACHI – very long sword (over 30 inches)

O-KISSAKI – large kissaki

O-MIDARE – large irregular hamon

OMOTE – signature side of the nakago

O-NIE – large nie

O-NOTARE – large wave patterned hamon

ORIGAMI – appraisal certificate

ORIKAESHI MEI – folded signature

OROSHIGANE – specially processed steel for making swords

O-SEPPA – large seppa (usually on tachi)

OSHIGATA – rubbing of the signature on the nakago

O-SURIAGE – a shortened tang with the signature removed

SAGEO – cord used for tying the saya to the obi

SAGURI – catch-hook on saya

SAIHA/SAIJIN – retempered sword

SAKA – slanted

SAKI – tip or point

SAKI-HABA – blade width at yokote

SAKI ZORI – curvature in the top third of the blade

SAKU – made

SAME’ – rayskin used for tsuka (handle) covering

SAMURAI – Japanese warrior or the warrior class

SANBONSUGI – “three cedars” (hamon with repeating three peaks)

SAN-MAI – three-piece sword construction

SAYA – sword scabbard

SAYAGAKI – attribution on a plain wood scabbard

SAYAGUCHI – mouth of the scabbard (koi-guchi)

SAYASHI – scabbard maker

SEKI-GANE – soft metal plugs in the tsuka hitsu-ana

SEPPA – washers or spacers

SHAKU – Japanese unit of measure approximately one foot

SHAKUDO – copper and gold alloy used for sword fittings

SHIBUICHI – copper and silver alloy used for sword fittings

SHIKOMI-ZUE – sword cane

SHINAE – ripples in steel due to bending of blade

SHINAI – bamboo sword used in Kendo

SHINGANE – soft core steel

SHINOGI – ridgeline of the blade

SHINOGI-JI – sword flat between the mune and shinogi

SHINOGI-ZUKURI – sword with shinogi

SHIN-SHINTO – New-New Sword Period (1781 to 1868)

SHINTO – New Sword Period (1596 to 1781)

SHIRASAYA – plain wood storage scabbard

SHITODOME – small collars in the kurikata and/or kashira

SHOBU ZUKURI – blade where shinogi goes to the tip of the kissaki (no yokote)

SHOGUN – supreme military leader

SHOTO – short sword (between 12 and 24 inches)

SHOWATO – sword made during the Showa Era (usually refers to low quality blades)

SHUMEI – red lacquer signature

SHURIKEN – small throwing knife

SORI – curvature

SUDARE-BA – bamboo blinds effects in hamon

SUE – late or later

SUGATA – shape of sword blade

SUGUHA – straight temper line

SUKASHI – cut out

SUN – Japanese measure, approx. one inch

SUNAGASHI – activity in hamon like brushed sand

SURIAGE – shortened tang

TACHI – long sword worn with cutting-edge down

TACHI-MEI – signature facing away from body when worn edge down

TAKABORI – high relief carving

TAKANOHA – hawk feather style of yasurime

TAMAHAGANE – raw steel for making swords

TAMESHIGIRI – cutting test

TAMESHI-MEI – cutting test inscription

TANAGO – fish belly shaped nakago

TANAGO-BARA – fish belly shaped nakago

TANTO – dagger or knife with blade less than 12 inches

TATARA – smith’s smelter for making sword steel

TO – sword

TOBIYAKI – islands of tempering in the ji

TOGARI – pointed

TOGI – sword polish or polisher

TORAN – high wave like hamon

TORII-ZORI – sword curve in the middle of the blade

TSUBA – sword guard

TSUCHI – small hammer/awl for removing mekugi

TSUKA – sword handle

TSUKA-GUCHI – mouth of handle

TSUKA-ITO – handle wrapping or tape

TSUKAMAKI – art of wrapping the handle of a sword

TSUKURI / ZUKURI – sword

TSUKURU – made by or produced by

TSUNAGI – wooden sword blade to display fittings

TSURUGI – double edged, straight sword

UBU – original, complete, unaltered tang (nakago)

UCHIGATANA – fighting katana

UCHIKO – fine powder used to clean sword blades

UCHIZORI – curved inward

UMABARI – horse needle

UMA-HA – horse teeth hamon

UMEGANE – plug used to repair kizu

URA – side of the nakago facing toward the body

URA-MEI – signed on the ura (usually the date)

UTSURI – reflection of temperline in ji

WAKIZASHI – short sword (blade between 12 and 24 inches)

WARE – opening in the steel

WARI-BASHI / WARI-KOGAI – chop-sticks

YAKI DASHI – straight temperline near the hamachi

YA-HAZU – arrow notch shaped hamon

YAKIBA – hardened, tempered sword edge

YAKIDASHI – hamon beginning just above the ha-machi

YAKIHABA – width of yakiba

YAKI-IRE – fast quenching of sword (tempering)

YAKIZUME – temperline in boshi with no turnback

YANONE – arrow head

YARI – spear

YASURIME – file marks on nakago

YOKOTE – line between ji and kissaki

YOROIDOSHI – armor piercing tanto

ZOGAN – inlay

ZUKURI – sword